Module 1 – What We Get from Medicines

Module Overview

It’s very easy to take medicines for granted. When people are questioning the price of drugs, it’s important to ensure they are aware of and reminded of the value modern medicines and vaccines bring – how they improve our lives, prevent and treat illness, extend our lifespans and provide a higher quality of life even if we have chronic illnesses.

This module provides an overview of those benefits, including:

- Increases in life expectancy

- Reduction in infant mortality and childhood diseases

- Changes in causes of death

- Implications of living longer

- Overall benefits of medicines to health and society

- Impact of new medicines in key therapeutic areas

- Flashback to 1960

- What we can learn from 1960

Module Objectives

To provide you with information and data to remind yourself and people with whom you interact of the great benefits we receive from medicines and vaccines – as individuals, families and as a society. This information forms an important foundation for people to understand and reflect on the value of medicines, not just their price.

After completing this module you will be able to:

- Describe improvements in life expectancy in Canada and its implications

- Explain the benefits derived from new medicines in key therapeutic areas

- Discuss the important changes that have occurred in healthcare since 1960

Increases in Life Expectancy

The fastest growing age group in Canada is of those over age 100. In just five years between censuses in Canada the number of centenarians increased more than 40%. This is quite a remarkable achievement.

In 1921, the average life expectancy in Canada was 57.1 years. Ninety years later, in 2011, it was 81.7, a gain of 24.6 years or almost 45%. Nearly half of that increase was recorded between 1921 and 1951, due to greatly reduced childhood mortality. That, in turn, was caused by tremendous improvements in public health and sanitation, a better and safer food supply and the ability to treat basic infections with the development of penicillin and other drugs. Since 1951, most of the life expectancy increase has come from improved ability to treat circulatory diseases, thanks in large part to the development of new and better medications to treat both cardiovascular disease risk factors and conditions themselves. Greater vaccination to prevent more diseases has also played a major role in improving the overall health of the population.

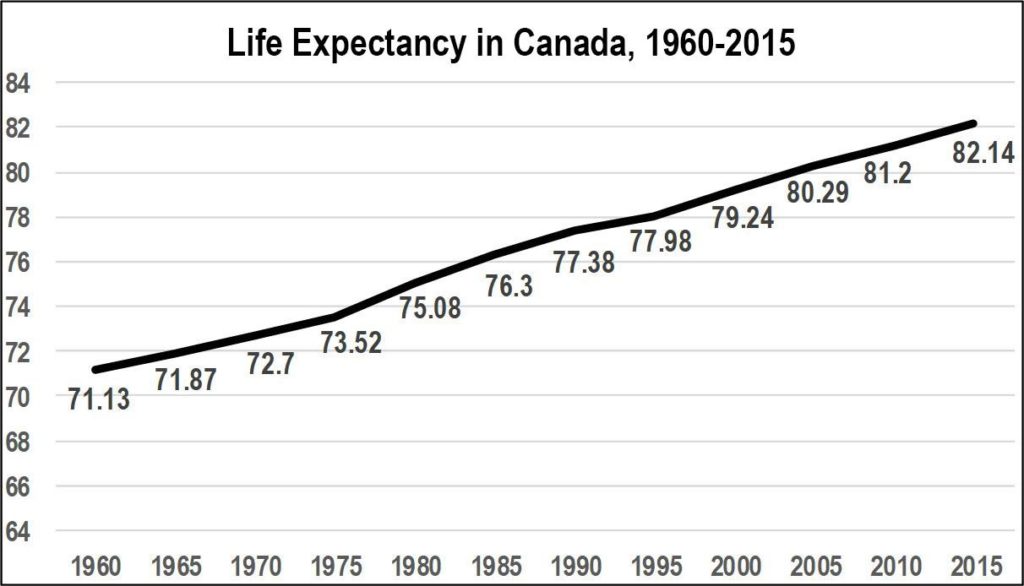

Within the lifetime of Canadians over 55, life expectancy rose by more than 11 years, from 71 years in 1960 to 82 in 2015 (see chart below). Life expectancy in Canada should continue to improve. By 2030, it is expected to be 86.0 for females and 81.9 for males.

Source: World Bank, from https://www.google.ca/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&met_y=sp_dyn_le00_in&idim=country:CA N:USA:JPN&hl=en&dl=en

The numbers are not improving just because fewer babies and children die. We can expect to live longer at every stage of life. In 1921, the average Canadian who reached age 55 could expect to live to age 75. Today, a 55-year-old can expect to live to 84, an important gain of nine years but one that has important implications for our healthcare system.

Reduction in Infant Mortality & Childhood Diseases

As noted above, one of the great causes for increased life expectancy through the first half of the 20th century was a drop in infant mortality. In 1901, the infant mortality rate in Canada was 134 per 1,000, meaning that about 1 in 7 babies died during their first year of life. By the end of the 20th century the rate was cut by 95%, to 5.5 per 1,000.

The development of new vaccines during the latter half of the 20th century has had a dramatic impact on the number and impact of childhood diseases. In 1953, before the introduction of the first polio vaccine, 9,000 cases of the viral disease were reported in Canada, most in children and often with devastating effects, such as paralyzed or deformed limbs, breathing difficulties or death. Twelve years later, after the introduction of the vaccine, only three cases were reported and in 1968 no cases of wild polio virus were reported in Canada. Thanks to vaccines, the disease had been eradicated in Canada, as smallpox had been before it.

Prior to the introduction of a measles vaccine in 1963, an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 cases occurred annually in Canada. In 2016, just 11 cases were reported in Canada. When the rubella vaccine was introduced in 1969, the incidence fell by 60,000 cases per year.

The introduction of the combined MMR vaccine (measles, mumps and rubella) in 1983 cut rubella cases from 5,300 per year from 1971-82 to fewer than 30 cases per year from 1988 to 1994. In 2016, just one case of rubella was reported in Canada and there were headlines when 30 cases of mumps were reported in Toronto and more from other small outbreaks in different cities because the disease is now such a rarity.

It is important that we not take the great public health benefits of vaccines for granted.

Changes in Cause of Death

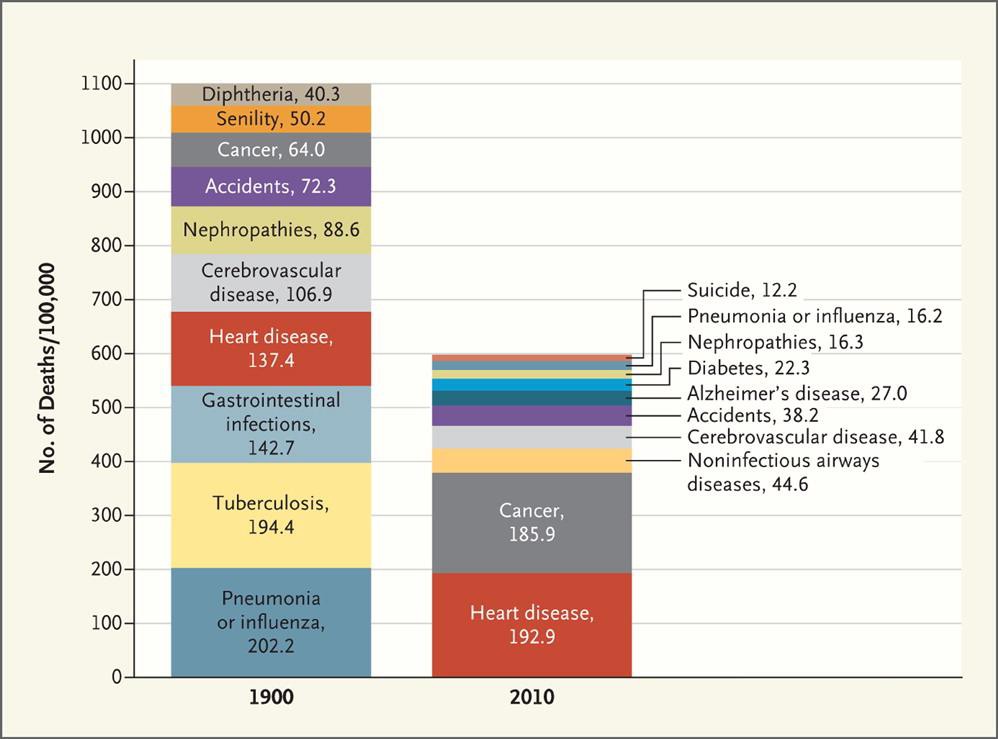

Developments of new medications and better public health have caused major changes in the number and causes of death over the past century. In 2012, The New England Journal of Medicine compared the numbers and causes of death in the United States between 1900 and 2010 (see chart).

The actual number of deaths per 100,000 population declined almost by half, from

1,100 in 1900 to 600 in 2010. The three leading causes of death in 1900 – pneumonia or influenza, tuberculosis and gastrointestinal infections – had become relatively minor causes of death by 2010 thanks in large part to both vaccines to prevent them and medicines to treat them. The two major causes of death that grew significantly are the leading causes of death today – heart disease and cancer. However, cerebrovascular disease (stroke), while still a significant cause of death today (third in Canada), has dropped significantly (by more than half) since 1900.

Number and causes of death in the United States per 100,000 population, 1900 vs 2010

Source: Jones DS, Podolsky SH and Greene JA, The Burden of Disease and the Changing Task of Medicine, N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2333-2338 June 21, 2012 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1113569. Accessed May 8, 2017 at: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1113569

In Canada, the leading cause of death is now cancer. According to statistics published in 2017 for deaths in 2013, cancer was responsible for 3 of 10 deaths (29.8%). Second is heart disease at 1 in 5 (19.8%), followed by cerebrovascular diseases (stroke) at 5.3%, chronic lower respiratory disease 4.7%, accidents 4.5% and diabetes 2.8%. As recently as 2000, however, the combination of heart disease and stroke caused more deaths than cancer (32.4% to 28.7%).

What changes are we likely to see in cause of death over the next 50 or 100 years? Will our new medications help us solve the riddles of cancer and heart disease?

Implications of Living Longer

The increases in cancer and heart diseases as leading causes of death mask the great progress made in treating all these conditions. More people are living long enough to develop cancers and heart disease rather than dying at younger ages of infections and infectious diseases. Living longer also increases the possibilities of developing chronic diseases which have greater incidence in older populations, such as lung/respiratory conditions and diabetes.

The number of Canadians with diabetes was 3.4 million in 2015, representing 9.3% of the population, and is expected to reach 5 million by 2025.56 One study showed that in Ontario the prevalence rate of diabetes increased by 69% from 1995 to 2005.

This and other chronic diseases – which, thanks in large part to medications, people are able to live with for decades in relatively good health – places very new and different burdens on our health system. Whereas in the past people tended to visit the doctor and hospital only when they were sick with an infection or disease, more and more such medical attention is devoted to preventing and treating chronic illnesses such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other respiratory ailments and heart failure. Excluding maternity cases, COPD is the leading cause of hospitalization in Canada and heart failure fourth, though heart failure is second for Canadians over age 65 (numbers 2 and 3 for all patients being heart attack and pneumonia).

Diet and lifestyle are also contributing to an epidemic of obesity in Canada, with tremendous current and future implications for our healthcare system, particularly compared to 50 years ago when it wasn’t really an issue at all. Since 1980, the number of adults with obesity in Canada has doubled, while the number of children with obesity has tripled. Canada ranks fifth for the number of adults with obesity and sixth for children with obesity among industrialized countries.

The cost in healthcare spending, and in lost productivity due to obesity, is estimated to be between $4.6 billion and $7.1 billion in Canada annually. To put things into perspective – that cost of obesity alone works out to about half the amount the public sector in Canada spends on ALL medicines ($12.5 billion in 2014). However, we hear much more about the necessity of reining in drug costs than we do about needing to save healthcare costs by reducing rates of obesity or, indeed, of reducing other activities that increase health spending.

Overall Benefits of Medicines to Health and Society

It’s very easy to take for granted overall the benefits of medicines to health and society. However, the benefits are huge, across a whole range of health conditions. When we feel run down because of a headache, we take an inexpensive over-the-counter pill and are able to complete our work day or enjoy our day off. When we have a life-altering condition such as Crohn’s disease, medicines can help us live long periods without serious symptoms and reduce the need for debilitating bowel surgery. When we have a life- threatening condition such as cancer, medicines can literally save our lives.

Society turns to medicines as the first and best option to meet many health challenges. When new threats emerge, such as SARS or Ebola, the search for treatments and vaccines quickly follows the initial public health efforts. New medicines were critical to reversing the trend of the deadly epidemic of HIV/AIDS in the early 1990s.

Researchers can often find new uses for old medicines that produce great benefit. The drug thalidomide, which 60 years ago proved the need for a strong and effective drug regulatory system when it caused birth defects in babies whose mothers had taken it for morning sickness, is now used as an effective treatment for the blood cancer multiple myeloma.

Medicines have a vital impact on reducing overall healthcare costs by preventing hospitalizations or the need for other medical interventions. They also help to reduce productivity losses from sickness by allowing people to recover and return to work, or not miss any work at all. A study by the Conference Board of Canada of just six classes of medications (ACE inhibitors, statins, biguanides, biological response modifiers, inhaled steroids and prescription non-nicotine smoking cessation aids) showed that in one year, Ontario’s expenditure of $1.22 billion on these treatments resulted in $2.44 billion of offsetting health and societal benefits, a ratio of two to one.

The Conference Board of Canada report also projected that this ratio will keep increasing for all six drug classes through to 2030, reaching five to one for four of the six classes by that time. As the report concludes, “Investments made to facilitate pharmaceutical innovation need to be viewed over the long term, as the return on investment increases with time.”

As we move into the future, it is also clear that pharmaceutical innovation will continue, allowing Canadians to benefit from new treatment. According to a report by IQVIA, leading the innovation through the near future will be medicines with novel mechanisms of action acting on underlying diseases processes or those that apply a mechanism already shown effective in one disease to another. Many new treatments are expected based on an improved understanding of the root causes of inflammation and immune response, such as new treatments to address issues of anti-microbial resistance. There is also hope for new treatments for long-term acquired chronic diseases such as Alzheimer’s and atherosclerosis which affect large and increasing numbers of people and drive large costs for the health system.

The future of new pharmaceutical innovation and the benefits it will bring to patients and the healthcare system is very bright.

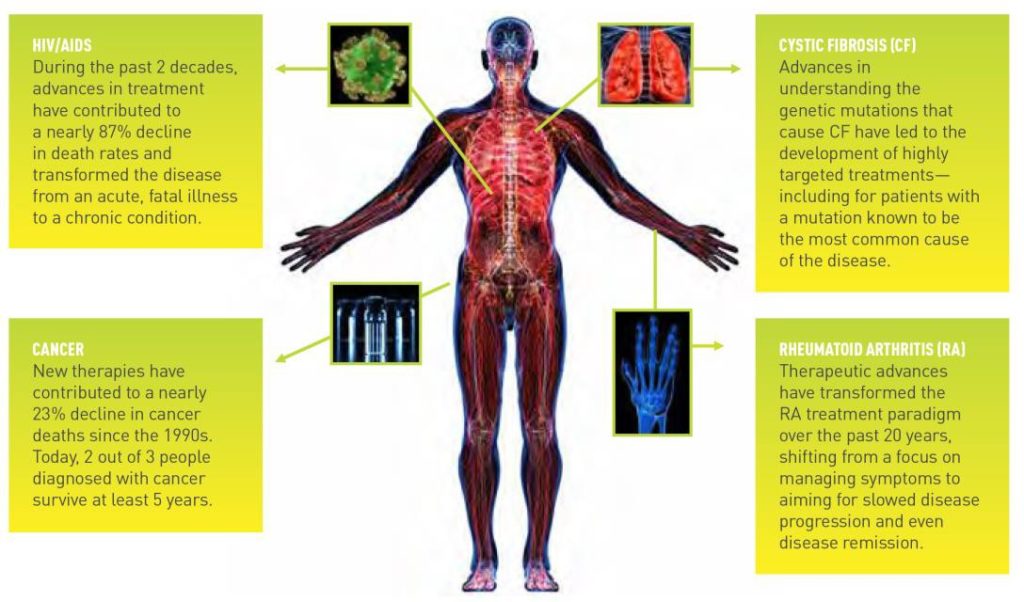

Impact of New Medicines in Key Therapeutic Areas

New types of medicines have had a huge impact in the ability to effectively treat – and sometimes eliminate or cure – a wide variety of diseases and conditions. Some of the major advances over the past 20 years in various leading conditions have been documented in some major research which we hope will be updated in the near future.

These areas include:

Cardiovascular Disease & Conditions

Medications along with education to promote healthier lifestyles have played a major role in dramatically reducing the death rate from many cardiovascular diseases and conditions. Canada reduced deaths due to circulatory diseases from 584 per 100,000 people in 1960 to an estimated 131 in 2009—a total reduction of more than 77% and an average decline of 3% per year. Only Australia managed a larger cut in its mortality rates—by an average of 3.3% per year.

New classes of treatments introduced in the 1990s and 2000s for controlling high cholesterol and high blood pressure – important risk factors for cardiovascular disease – have had an important impact on helping more Canadians control those conditions. For example, between 1994 and 2003 – a decade during which many new treatments for high blood pressure were introduced, including once-a-day formulations – the percentage of Canadians who had high blood pressure that was untreated fell by more than half from 32% to 15%.

A 2005 study showed that each death avoided by treating a patient with coronary disease yielded 7.5 additional years of life, while each death avoided by changing risk factors (mainly smoking, controlling blood pressure and cholesterol) yielded 20 additional years of life. Overall, risk factor changes accounted for 55% to 60% of the decline in mortality, but almost 80% of the life-years gained.

New medications have made it easier for Canadians to treat major cardiovascular risk factors, such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol, including newer treatments that have fewer side effects and easy once-daily dosing. Major landmark studies conducted by pharmaceutical companies to study these new treatments have led to important findings, such as the 4S trial (Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study) in the 1990s which showed the connection between lowering cholesterol with the statin simvastatin and reductions in mortality and morbidity. Other major landmark studies, such as ASCOT-LLA with atorvastatin, showed similar results.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) – a separate and very different condition from osteoarthritis which is generally due to wear and tear and inflammation in the joints – is a systemic autoimmune disorder that causes chronic inflammation of the joints as well as other organs in the body.

Uncontrolled, RA is typically a progressive illness characterized by joint swelling, pain and joint destruction which can result in disability and shortened lifespan.

The introduction of biologic TNF (tumour necrosis factor) inhibitor treatments for RA over the past 15 years has provided immense benefit to patients in reducing pain and disability, permitting more to live a more normal and productive life. Some people even achieve remission on these new therapies.

Biologics have also meant fewer other major healthcare interventions to help people with RA. According to a US study, the total number of hip replacement surgeries doubled and knee replacement surgeries tripled in the US between 1993 and 2008, due to a number of factors, including ageing of the baby boomers, increased rates of high-impact exercise such as running and increased unwillingness of people to live with the pain and disability of osteoarthritis. However, following the introduction of three innovative biologic therapies (TNF inhibitors) there was a 32% and 24% reduction in rheumatoid arthritis being the primary reason for total knee replacement and total hip replacement surgeries, respectively.

Gastrointestinal Conditions

One of the most common reasons for surgery in Canada in the 1960s was for peptic ulcers. In the 1970s, the development of H2 antagonist medications dramatically reduced that need, with better results for patients. In the 1980s, the further discovery of the role of the bacterium H. pylori in causing stomach ulcers led to antibiotics being the simple treatment for many ulcers, resulting in ulcer surgery becoming relatively rare.

The development of biologic medicines to treat inflammatory bowel disease (primarily Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) has had an enormous positive impact on people with these conditions, allowing them to live far more normal lives and, in many cases, avoiding life-altering surgery to remove parts of their bowel. Canada has among the highest rates in the world of these diseases.

Diabetes

Until the discovery and development of insulin in Canada in the 1920s, diabetes was a fatal disease. As the disease has become better understood, and the distinction understood between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, more treatments have become available, including many to slow advance of Type 2 disease in its early stages to delay the need for many patients to take insulin. Particularly important have been techniques developed in the 1970s and 1980s to measure blood glucose levels and drug treatments to reduce them. Newer treatments make it easier for patients to manage their condition, such as by requiring less frequent and easier methods of administration, thereby improving adherence to treatment and, ultimately, better outcomes.

Mental Health Issues

While there remains a very large burden and stigma surrounding mental health issues in our society, their treatment has been profoundly changed and improved by numerous new classes of medications in the second half of the 20th century. As society grapples to better understand the complexity and need for empathy for those suffering from mental health issues, medication can play an important role in helping to stabilize patients and, in some cases, reduce the need for aggressive interventions. Important classes of medicines are now available to effectively treat the prevalent conditions associated with depression, anxiety and psychoses, making a vitally important difference in patients’ lives.

HIV/AIDS

The sudden arrival of mysterious and untreatable immune-system related illnesses in the 1980s was seen as a dangerous plague that would kill untold numbers and overwhelm healthcare resources. The first two deaths in Canada from this mysterious ailment were reported in 1980 and the number of deaths increased steadily for the next 15 years.

At first the cause of what was called Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) was unknown, but the discovery of its cause from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) soon led to the development of effective treatments, first introduced in 1995, soon followed by combination “cocktail” treatments or highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

The impact has been profound. In Canada, deaths from AIDS peaked at 1,516 in 1995 (more than four per day), the year of the first effective treatment introduction. Just two years later the number had dropped by two-thirds to 501 and 10 years later, in 2005, to 113. In 2013, only 31 deaths from AIDS were reported in Canada.

While still an important health issue, HIV infection is now effectively a very treatable chronic condition in Canada and elsewhere, thanks to the availability and generally effective accessibility of drug treatments.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is a virus transmitted through blood and other bodily fluids. It can stay in a body for a long time without causing major symptoms, but almost inevitably will cause liver damage and disease. When liver damage becomes severe, the only treatment is a liver transplant. New anti-viral treatments, however, have been shown to effectively eliminate hepatitis C in most patients treated, effectively curing them. This not only prevents future liver damage in the treated patient, but also prevents them from passing on the infection.

Cancer

Even though cancer has become the leading cause of death in Canada, as noted above this is a function of Canadians living longer lives and the declining rates of death from other causes, such as cardiovascular problems. The Canadian Cancer Society says one of every two Canadians will be diagnosed with cancer in their lifetime, with more than 200,000 cancer diagnoses made in Canada every year. The Society’s 2017 report on Canadian Cancer Statistics estimated that in 2008, cancer was responsible for $3.8 billion in direct healthcare costs and a further $586 million in indirect costs from lost productivity. As well, cancer was the costliest of all illnesses in terms of lost productivity due to death.

Important progress has been made in extending the lives of people with cancer. Five-year age-standardized net survival for all cancers in Canada has risen 7.3 percentage points from 53.0% for cancer diagnosed in 1992-94 to 60.3% for cancer diagnosed in 2006-08. Every major cancer has seen improvements in survival, some substantial. The largest increases in five-year survival rates over that time period have been in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (16 percentage points), leukemia (15 percentage points) and multiple myeloma (14 percentage points).

Although increased screening has helped improve survival (due to discovering it at an earlier stage), and cancers have been prevented through public health initiatives (such as reducing smoking rates), an additional major reason for gains in survival rates has been advances in medications. In fact, a 2015 study shows that pharmaceutical innovation in the absence of pharmaceutical innovation during the period 1985–1996, the premature cancer mortality rate would have increased about 12 % during the period 2000–2011.

There have been two major new advances in cancer medications in recent years, targeted or personalized therapies and immunotherapies:

Targeted (or personalized) therapies: These treatments act on a very specific genetic or molecular target that is responsible for helping the cancer to continue to grow. Patients can be screened in advance to find out if their cancer is of a particular genetic form and given a medicine that has been specifically designed to treat that type of cancer, if such a medicine exists. This is why these are also called “personalized therapies.” Generally, very positive response rates and encouraging results have been seen with such therapies. Numerous very specific targeted therapies have now been approved to treat many cancers but particular progress in targeted therapies has been seen in lung cancer, the leading cancer killer (by far) in Canada.

Example: One of the first targeted therapies was Gleevec® (imatinib, Novartis) for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), approved in 2001. It is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the BCR-ABL1 oncoprotein. It helped many patients, some dramatically, but it was then found to be even more effective if started earlier in the disease process. As well, other types of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been developed that have proven successful in patients who didn’t respond to or became resistant to imatinib. As a result, the five-year relative survival rate rose from 21% in those diagnosed with CML in 1973-79 to 80% in those diagnosed from 2001-08, and to 91% in those recently diagnosed who were less than 50 years old when diagnosed.

Immunotherapies: Cancer cells are similar in many ways to other pathogens that attack the body (such as viruses) but are fought off by the body’s immune system. More than a century ago, doctors noticed that cancer patients whose immune system was stimulated to fight off a more routine infection would often also see an improvement in their cancer. Within the past decade, new therapies have been developed that work by turning off different “checkpoint” switches that hold back or inhibit the body’s immune system. Turning off these checkpoints thus makes the immune system more active which can be enough in some patients to destroy the cancer cells. Though not every patient responds to these therapies, among those who do there can be very dramatic responses. This is a very promising and active new area for cancer therapies.

Example: Immunotherapies have helped many patients with metastatic melanoma, a very serious skin cancer with a normally very poor prognosis. In August 2015, former US President Jimmy Carter announced he had stage 4 melanoma which had spread to his liver and brain. This situation would in the past have caused death within months. President Carter had surgery on his liver, radiation treatments and received a new immunotherapy treatment. In February 2016, after four months of treatment, he announced he was cancer-free and continuing his normal activities, though they are far more than those of most people in their 90s (he was born in 1924).

Further innovative research into the use of viruses to attack and kill cancer cells and stimulate an anti-cancer immune response is being conducted in Canada, led by Dr. John Bell at The Ottawa Hospital. There is a strong possibility that such “biotherapeutics” could become successful cancer treatments in the future.

Cancer vaccines: Cancer has also been addressed innovatively recently by seeking to prevent it through the use of vaccines. The vaccines Gardasil® (Merck) and Cervarix™ (GlaxoSmithKline) prevent human papilloma virus (HPV) infections that cause cervical cancer. Since HPV vaccinations programs began in the US , the rate of HPV infection in girls age 14-19 has fallen by almost two-thirds, from 11.5% to 4.3%.

Preventive Vaccination

When people think of preventive vaccinations, they likely first think of absolutely game- changing early vaccines for smallpox (1796) and polio (1954), then for measles, mumps and rubella (1960s) and combined into one in the 1970s. Since then, however, there have continued to be important advances in vaccines beyond the cancer vaccines mentioned above. These include vaccines against varicella (chickenpox), pneumonia, shingles and rotavirus. All of these have made significant contributions to disease prevention and thus avoiding costs to the healthcare system.

Surgical Aids

Medicines have a key role to play in permitting and helping ensure success of numerous surgical interventions. These include:

- Anti-infectives: Many surgeries would not be possible, or would result in a lot more complications due to infections, without the ability to use anti-infective medications to prevent and treat post-operative

- Anti-clotting medications: A major risk of many surgeries, particularly those for hip and knee replacement, is the development of potentially fatal blood clots. New medications offer much easier and effective ways to manage the risk of blood clots, making such surgeries safer for

- Anti-rejection medications: Organ transplants, which have become routine surgical procedures that save thousands of lives every year, would not be possible without medications taken by organ recipients to prevent their body’s immune system from rejecting the transplanted

Medicines are Transforming the Treatment of Many Diseases

Illustration from:Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), PhRMA 2016 Profile, p. 7, accessed May 18, 2017 at: http://phrma-docs.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/biopharmaceutical-industry-profile.pdf

Flashback to 1960

Let’s wrap up this module with a flashback – to the “good old days” of 1960, almost 60 years ago, but within the lifetime of about a third of Canadians. Your parents may

have been kids, your grandparents in their prime, or even younger. Anyone who is now over 65 would remember it well.

John Kennedy was running against Richard Nixon to become President of the US. John Diefenbaker was Prime Minister of Canada. No one had been into space. Air travel was a luxury for the rich. Television was in its infancy. Elizabeth II was Queen, already into the ninth year of her reign on her way to becoming the longest-reigning British monarch in history.

Medically, what did 1960 look like?

Most important, while people often had longtime family doctors, they really only consulted them or went to the hospital with acute illnesses or injuries. The medical system was to treat disease, infections, cuts, fractures and other traumas. There were few tests to take or worry about unless there was an onset of illness.

Canadians were also generally responsible for paying for their own medical care, either doctor visits, hospitalizations or medications. Many had private health insurance to cover major costs – often through their work or employer – but many did not. Doctors and hospitals forgave a lot of bad debts. Many people simply did without healthcare they needed because they couldn’t pay. Canada’s universal healthcare system did not come into effect until the late 1960s.

Children of 1960 could expect that a number of fellow students in their school – particularly older ones – would be disabled by polio. They would perhaps have a paralyzed arm or a limp due to a disability in a leg. They had caught the dreaded disease before the miracle vaccine became available in Canada.

Children would often miss a week or two of school because they were home with mumps, measles, rubella or chicken pox. Some boys who got mumps around puberty were left sterile, though they wouldn’t know it until they tried to have children.87 Women not wanting to have children in 1960 were interested to hear a new contraceptive pill had just become available in the United States (though they would have to wait until 1969 for its sale to be authorized in Canada).

If you thought you had seasonal allergies, you could be tested and maybe take a whole series of injections to try to help it. There were no pills. For mental health issues, little was known and few effective treatments were available, putting strain and stigma on patients and families; many people were simply institutionalized. You might hear that the father and husband in a neighbouring house, a healthy-looking man in his 40s, was on a strict diet to treat his stomach ulcers. You’d be surprised to hear a few weeks later that he had died from uncontrolled bleeding following his stomach surgery to repair the ulcers.89 Another neighbour in his 60s, who had often said he should watch what he ate (but didn’t) because his doctor said he had “high sugar,” might appear one day in a wheelchair, his leg amputated below the knee from the circulatory complications of his uncontrolled diabetes.

Your doctor might tell you that you had high blood pressure and give you a diuretic pill to take several times a day, but results were not great and you’d be running to the bathroom all the time so you would likely stop taking it since the “cure” seemed worse than the symptomless “disease.” It was distressingly regular news to hear that a middle-aged man, and sometimes a woman, had suddenly died of a heart attack.

That’s just how it was.

What We Can Learn From 1960

It’s important to understand this medical environment of 1960 because it echoes to us today in one very vital way: medicines were not then and are still not part of the universal medicare plan developed in Canada in the 1960s because it was considered that it was more feasible to cover physician and hospital costs as the “initial minimum” for a universal health plan and possibly move on to covering medicines (and other services such as dental care) in the future.

Despite the lack of a universal national pharmacare program, Canada’s federal, provincial and territorial governments have all implemented public pharmacare programs. In addition, the majority of Canadians have access to drug coverage through work under a private drug program. As a result, as we will see in more detail in Module 3, nearly all Canadians have access to some form of drug insurance coverage. That said, even with drug coverage, Canadians are still responsible for paying at least a part of their drug costs. For this reason, Canadians are much more aware of the prices of drugs than any other type of healthcare services.

We don’t often hear questions about how much a certain type of surgery or hospital treatment costs because people don’t have to worry about how they will pay for them. For example, it costs on average $92,000 a year to give someone hemodialysis when they have kidney failure, something which is diagnosed in about 5,500 Canadians each year.91 Just those people newly needing dialysis will cost the health system about $500 million in their first year. But few people know or question that cost because it is all covered by medicare.

There is also much confusion on the issue of drug prices in Canada in general. Many Canadians don’t always realize that medicines are not always part of the medicare system or they are unaware that some medicines may be covered while others may not.

The following modules of the course will discuss various aspects of our medical and legal system that impact those prices.

But a key element of the discussion of drug prices is to build recognition and understanding of the immense benefits we all receive from the thousands of medicines that are now available to treat and prevent so many medical conditions, allowing us all to live longer, better and more productive lives.

Yes, that comes at a cost, but we must never lose sight of the immense benefits.

Module Review

The length and health of Canadians’ lives has changed dramatically over the past century. Average life expectancy increased by 45% from 1921 to 2011 and a Canadian who lives to 55 can expect to live to 84. This has important implications for our healthcare system.

While we have eliminated some of the major causes of death from a century ago, our longer lives and greater affluence have resulted in great increases in rates of cancer as well as obesity and diabetes, again with important implications for our healthcare system.

New medicines have had a tremendous positive impact on many therapeutic areas. One of the great success stories is in cardiovascular diseases and conditions, with the death rate from these conditions declining at a rate of 3% per year for the last 50 years – a total reduction in the death rate of 77% from 1960 to 2009. New medicines have played a major role in reducing cardiovascular risk factors and treating diseases.

New medicines and vaccines have also contributed to other important improvements in care and prevention in diabetes, mental health issues, rheumatoid arthritis, hepatitis C and in facilitating many types of surgery. The role of new medicines in combatting the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s was unprecedented and amazingly successful.

Though cancer rates are up due in part to people living longer, new treatments have contributed to improving survival rates in various ways. Two important new types of cancer treatments are targeted therapies and immunotherapies, as well as vaccines against cervical cancer caused by HPV.

The practice of medicine has come a long way over the past fifty years, with pharmaceuticals and vaccines playing a key role in improving and saving lives and helping Canadians live longer and healthier than ever. In addressing price and cost issues, in terms of how individuals, businesses and health systems pay for drugs, we must always keep in mind the tremendous benefits we receive from them.